The Connection Between Leaky Gut and Leaky Brain

Mindd Foundation

The Connection between Leaky Gut and Leaky Brain

The intestines and the brain could not be further apart anatomically within our bodies. They are known to have different roles, with the brain often thought of as the ‘master’ and valued more highly than the gut.

Leaky Gut and Leaky Brain?

However, research has shown that the gut and brain are intricately connected. They even communicate regularly through a ‘nervous system language’ of small molecules and proteins. And both have a direct effect on overall health.1So, when either the brain or gut are disturbed, it can create physical and physiological imbalances. This may lead to a gastrointestinal complaint, anxiety or depression, or all of these.This situation can occur when someone suffers from what is often called ‘leaky gut syndrome’.

Leaky gut – syndrome or symptom?

Leaky gut syndrome is not a medically diagnosed condition. It is a term used when the intestinal wall has increased permeability or hyperpermeability.

The intestines are designed to act as a barrier to the internal environment of the body. They provide protection from potentially dangerous molecules, such as pathogens and toxins.

The problem occurs when the intestinal barrier is damaged, due to certain triggers, oxidative stress or inflammation. The gates, called tight junctions, between the epithelial cells that make up the intestinal wall open up. This means substances that would normally stay in the intestine or be excreted by the body, can travel into the inner layer of our intestinal wall and our blood stream. The intestine is more permeable, it is ‘leaky’, and bigger particles can fit through.2

This stimulates the immune system and the release of inflammatory mediators against these substances. These molecules, which are now classed as foreign or dangerous, may be the healthy bacteria that normally live in intestines or particles of food normally eaten. This process can trigger more inflammation, allergic responses, further increases in intestinal permeability, changes in nervous system function and opioid type reactions, affecting mood and behavior.3

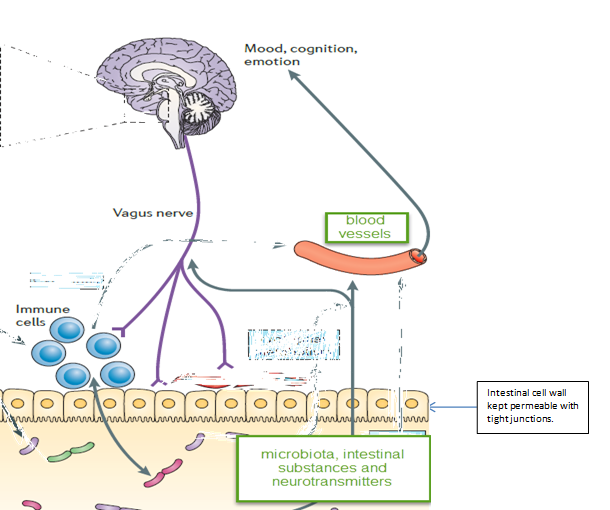

The gut and brain axis – Leaky Gut and Leaky Brain

The brain and gut communicate in a bi-directional manner. Disturbances in the brain from either physical or psychological stress affect gut function, while imbalances in the gut environment can produce behavioural and neuro-chemical changes.3

The gastrointestinal system contains its own nervous system – the enteric nervous system. It is through this system, and a nerve called the vagus nerve, along with endocrine (hormones) and immune pathways, that researchers believe the gut communicates with the brain.4

The gastrointestinal enteric nervous system also regulates intestinal permeability.3

Diagram adapted from: Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13(10):701-12.

The micro-organisms residing in our intestines also play a role in nervous system health and function. Recent research shows that the gut bacteria communicate electrically with each other through proteins called ‘ion channels’, just like the nerve cells in the brain.5

Additionally, 90% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut.

The neurotransmitter serotonin is important for healthy mood and sleep. It appears intestinal cells called enterochromaffin (EC) cells, which produce serotonin, may rely heavily on gut microbes for this function.6

Therefore, a healthy intestinal wall and a balanced gut microbiota are crucial to maintain the intestinal barrier and reduce the risk of gastrointestinal and neurological conditions.

Neurological conditions related to intestinal permeability

Studies have associated ‘leaky gut’ with the following conditions:

- schizophrenia

- autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

- bipolar disorder

- depression

- rett’s syndrome

- anxiety

- parkinson’s disease3

In regards to ASD, animal models designed to replicate ASD symptoms show gut barrier disturbances. In one human study, 36.7% of the 90 children with ASD tested, displayed abnormal intestinal permeability compared to relatives and controls.3

However, studies testing intestinal permeability in individuals with ASD have had mixed results. This potentially highlights variability within the condition and the need for individual testing and treatment.

One concern with ASD is the effect of opioid peptides (protein fractions) from cow’s milk (casein) and gluten. These fractions are supposed to be broken down in a healthy gut environment by digestive enzymes, such as dipeptidyl peptidase IV, but their absorption into the bloodstream may be increased with intestinal permeability.7

Opioid peptides can disturb gut function and increase pain and constipation. In the brain, these peptides may be linked to developmental disturbances, learning and interpersonal skill difficulties, and behavioural problems indicative of ASD.7

These peptides and intestinal permeability have also been linked to schizophrenia.3,8

What triggers intestinal permeability?

There are many potential causes for ‘leaky gut’, including:

- stress, physical or physiological

- gliadin, a protein component of gluten

- casein, cow’s milk protein

- food additives

- nutritional deficiencies

- dietary allergens

- alcohol

- parasitic and bacterial infection

- imbalanced microbiota (gut microbes)

- chemotherapy

- injuries and burns

- autoimmune conditions

- some medications, such as non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin

- modern food processing.2,3,9,10,11,12,13

Therapies for intestinal permeability

There are also many nutritional and herbal therapies available for repairing the intestinal barrier, reducing oxidative damage and inhibiting inflammatory processes.

All treatments need to be individualised by a qualified healthcare practitioner to each patient according to diagnostic testing, severity, symptom picture and genetic and family history.

Zinc

L-glutamine

Curcumin (Rapin)

L-arginine

N-acetyl glucosamine

Amino acids/protein

Probiotics and prebiotics

Saccharomyces boulardii

Digestive enzymes

Marshmallow root

Slippery Elm

Licorice root

Pectin

Aloe vera

Quercetin

Dietary interventions, such as gluten free, dairy free diets

References

- Toh MC, Allen-Vercoe E. The human gut microbiota with reference to autism spectrum disorder: Considering the whole as more than a sum of its parts. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26309.

- Rapin JR, Wiernsperger N. Possible links between intestinal permeability and food processing: A potential therapeutic niche for glutamine. Clinics (São Paulo, Brazil). 2010;65(6):635-43.

- Julio-Pieper M, Bravo JA, Aliaga E, et al. Review article: Intestinal barrier dysfunction and central nervous system disorders–a controversial association. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(10):1187-201.

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13(10):701-12.

- Prindle A, Liu J, Asally M, et al. Ion channels enable electrical communication in bacterial communities. Nature. 2015;527(7576):59-63.

- Yano Jessica M, Yu K, Donaldson Gregory P, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell.161(2):264-76.

- Wakefield AJ, Puleston JM, Montgomery SM, et al. Review article: The concept of entero-colonic encephalopathy, autism and opioid receptor ligands. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(4):663-74.

- Lister J, Fletcher PJ, Nobrega JN, et al. Behavioral effects of food-derived opioid-like peptides in rodents: Implications for schizophrenia? Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;134:70-8.

- Leclercq S, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, et al. Role of intestinal permeability and inflammation in the biological and behavioral control of alcohol-dependent subjects. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(6):911-8.

- Pavlidis P, Bjarnason I. Aspirin induced adverse effects on the small and large intestine. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(35):5089-93.

- Lerner A, Matthias T. Changes in intestinal tight junction permeability associated with industrial food additives explain the rising incidence of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(6):479-89.

- Stachowicz-Stencel T, Synakiewicz A, Owczarzak A, et al. Association between intestinal and antioxidant barriers in children with cancer. Acta Biochim Pol. 2012;59(2):237-42.

- Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: Consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012;10:13.