Anyone who has studied the immune system in depth has a deep appreciation of the intricacies, complexities and vast functions of this defensive network of protective structures and processes.

It is arguably one of the most challenging systems of human anatomy and physiology to study; the seemingly limitless cell populations, biochemical reaction cascades and molecular categorisations of the immune system all require great attention to detail to understand them well.

Ultimately, the immune system serves to protect us from both infectious and certain non-infectious diseases. However, the role of our immune system is targeted at significantly more human health issues than attacking pathogenic microorganisms. This system serves us at almost every level of our health; many other physiological systems rely on the strength of our immune system to operate correctly.

This is why immunological disorders are central to the core principles of the MINDD Foundation.

Anatomy of the Human Immune System

A network of cells, tissues, nodes, nodules, ducts and vessels scattered throughout your body, the immune system responds to everything from invading microorganisms through to foreign tissues and cells (including cancerous cells). The immune system performs much of its physiological functions via lymphatic tissue. The lymphatic system is sometimes described separately to the immune system; however, both work together for immune defence.

Spanning all regions of your body, the lymphatic network of vessels, capillaries, tissue and nodes primarily transports lymphatic fluid from peripheral organs and tissues before it is returned to general blood circulation. Lymphatic tissue and nodes are responsible for screening this fluid for pathogens, abnormal cells and other cellular complexes deemed to be ‘waste’ by the body. This ensures lymphatic fluid entering the general circulation is necessarily cleaned of unwanted and unnecessary immune debris.

Lymphatic tissue is arguably some of the busiest tissue in the body. Lymphatic tissue located within specific skeletal tissue is haematopoietic (blood cell producing). Your five tonsils (2 paired, 1 singular) are ideally located for their role in oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal defence. Masses of lymphatic tissue located in the ileal region of the small intestine known as Peyer’s Patches monitor digestive content for possible pathogens. The upper left abdominal quadrant of your body is the location of your spleen, an organ involved in screening blood for infections, abnormal cells and immune complexes. Immediately anterior to the heart is the Thymus gland. Very active in childhood and adolescence, the Thymus is involved in contributing to the ‘memory’ aspect of immunity, knowing to which infections and immunisations one has been exposed.

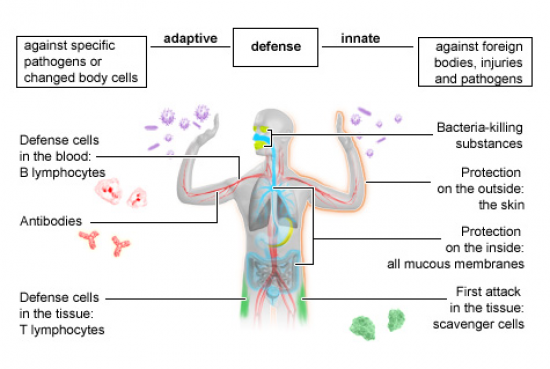

Adaptive and Innate Immunity

While possibly not as physiologically complex as adaptive immunity, innate immunity is critical for the protection of other sensitive, specialised and vital organs. Innate immunity involves secretions such as mucus, tears, acids, saliva, sebum and cerumen (wax). Mucous is produced not only in the respiratory system but also in the gastrointestinal system and reproductive system for this reason. Fever and inflammation are both examples of innate immunity, and both signify an attempt by the body to speed up the immune system, slow the reproduction of a pathogen, prevent the spread of localised infection and deliver cells of the immune system to an area of infection or damage.

Collectively, innate immune responses are not selective; the hallmark of these responses is their ability to regard all pathogens, physical tissue destruction and atypical cells as a problem. Without healthy innate immune mechanisms, your general blood circulation can be accessed by invading microbes, meaning infections spread easily. Nutrition, herbal medicine, acupuncture, manual therapies and lifestyle medicine is essential to buttress these defences to work in your favour.

Adaptive immunity involves responses that are highly specialised and targeted toward a specific pathogen or antigen (foreign substance). Adaptive immune mechanisms are those engaged in providing the body with lasting, sometimes life-long protection from certain infections. The ability to distinguish foreign tissue from ‘self’ tissue is a hallmark of the adaptive immune system. When one’s immune system responds to a normal healthy tissue structure as ‘foreign’ and reacts with destruction, the ensuing disorders are known as autoimmune diseases.

Cells of the Immune System

As stated earlier, the cells of your immune system are produced in the red bone marrow. After a series of maturation events occurring in the Thymus, general blood circulation or other lymphatic tissues, the cells of your immune system comprise the following:

- Neutrophils

- Lymphocytes

- Monocytes

- Eosinophil’s

- Basophils

Each category has multiple cellular subtypes; some so specific and diverse; there are hundreds in each category. While many are involved in the innate immune defences of inflammation and fever, others are so specialised they only respond to a specific species of microbe or antigen (foreign protein).

Immunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency is a significant health issue; the incredibly vast structures, cells and pathways of immune responses mean that immune compromise involves any and many parts of the immune system. Immunodeficiency disorders include the following:

- Inherited: these are genetic disorders running in families. Examples include diseases affecting the body’s ability to synthesise antibodies during infections. These disorders are rare; some are lethal due to the inability to control acute infection. Examples include X-linked agammaglobulinaemia’s, severe combined immunodeficiency, common variable immunodeficiency and ataxia telangiectasia.

- Acquired: this occurs due to other pathological events or malnutrition. HIV infection, cancer, splenectomy and diabetes are all associated with diminished immune strength. Nutrition and lifestyle medicine warrants particular attention, as both contribute heavily to both the power and adaptiveness of your immune responses in all phases of life, from the neonatal period to old age.

Complementary and Integrative Health Perspective

For those who do not suffer from a chronic illness with severe consequences for immunity, it is the immune system that does a beautiful job in keeping us healthy.

For some people, autoimmune diseases threaten the quality of life and diminish our wellbeing. Autoimmune diseases range from arthritic syndromes, such as rheumatoid arthritis (where the immune system mistakes collagen for abnormal tissue), through to autoimmune conditions which are very difficult to manage, including Scleroderma and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE).

Allergies and recurrent or low-grade infections seem to plague modern society. Allergies occur when the immune system ‘tags’ and over-reacts to proteins of everyday substances from plants, foods and animals. Essentially, the immune system should be able to deal with these antigens without ‘over-reacting’. Modern diets and lifestyle almost certainly contribute to the drastic increase in allergies and atopy.

Those with generally robust health who invest time and effort into their health may regard an infection as a ‘failure’ of their immune system. While dealing with a mild infection, influenza or gastroenteritis is not enjoyable, contracting these infections does not represent the failure of the immune system. Recurrent infections, persistent or chronic fatigue after infections and failure to thrive in children should all be investigated further.

Complementary and Integrative medical practices can support the functions of the immune system at various levels. There is no one single practice, food, supplement or lifestyle intervention that will suddenly ‘boost’ the immune system. Immune responses are so intricate, multi-layered and involve so many different cells, reactions and tissues that a long term approach is required to support immune health, usually from many different clinical angles including nutrition, exercise, anti-ageing, detoxification, psychological support and medication.

Sustaining Strong Immunity

- Do not smoke. A host of nutrients are depleted through cigarette smoking, but the destruction of innate immune defence structures in airways is exceptionally problematic for smokers

- Exercise regularly, but not in the extreme. The exercise that is extreme enough to cause stress on the body can act as a stressor, releasing cortisol (an immune suppressant). Exercise that depletes muscle mass is known to deplete the immune system

- Maintain a healthy weight. This is not only in regards to weight loss but losing excess fat as opposed to lean body mass (muscle) and gaining weight (both fat and muscle mass) in those who are underweight. Both healthy fat and protein stores in muscle tissue are essential for strong immune health

- Have good sleep hygiene. Without question, healthy and restful sleep is protective for your immune system. Without adequate rest, we do not recover well from infection; we run our body on energy reserves and do not give our body sufficient time to repair damage while asleep

- Eat nutrient-dense foods. Micronutrient malnutrition is extensive, even in affluent countries and societies. A diet low in variation (common in children and the elderly) is one possible cause. The quality of foods ingested, or a diet high in processed foods is another. Diets low in protein are renowned for compromising the immune system

- Supplement where needed (with the help of a practitioner). The minerals zinc, selenium, iron and copper, are all essential for sustaining healthy immune responses. In terms of vitamins, A, D, E, B2, B6 and C all support accurate immune responses in animal studies

Written by Annalies Corse BMedSc, BHSc

References

- Alberts, B. et al. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th Ed). Chapter 24: The Adaptive Immune System. Garland Science, New York.

- Kau, A. et al. (2011). Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature. 474: 327-336.

- Lange, T. et al. (2010). Effects of sleep and circadian rhythm on the human immune system. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1193: 48-59.

- Legrand, N. et al. (2006). Experimental models to study development and function of the human immune system in vivo. Journal of Immunology. 176 (4): 2053-2058.

- Segerstrom, S. et al. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of thirty years of enquiry. Psychological Bulletin.

- Wiesner, J. and Vilcinskas. A. (2010). Antimicrobial peptides: the ancient arm of the human immune system. Virulence. 1 (5): 440-464.