Microbiota, Microbiome, Gut Flora, Intestinal flora.

These scientific phrases commonly spoken by microbiologists are now becoming more widely used.

The terms gut flora and intestinal flora are old terms. The term ‘flora’ technically refers to any species belonging to the plant kingdom.

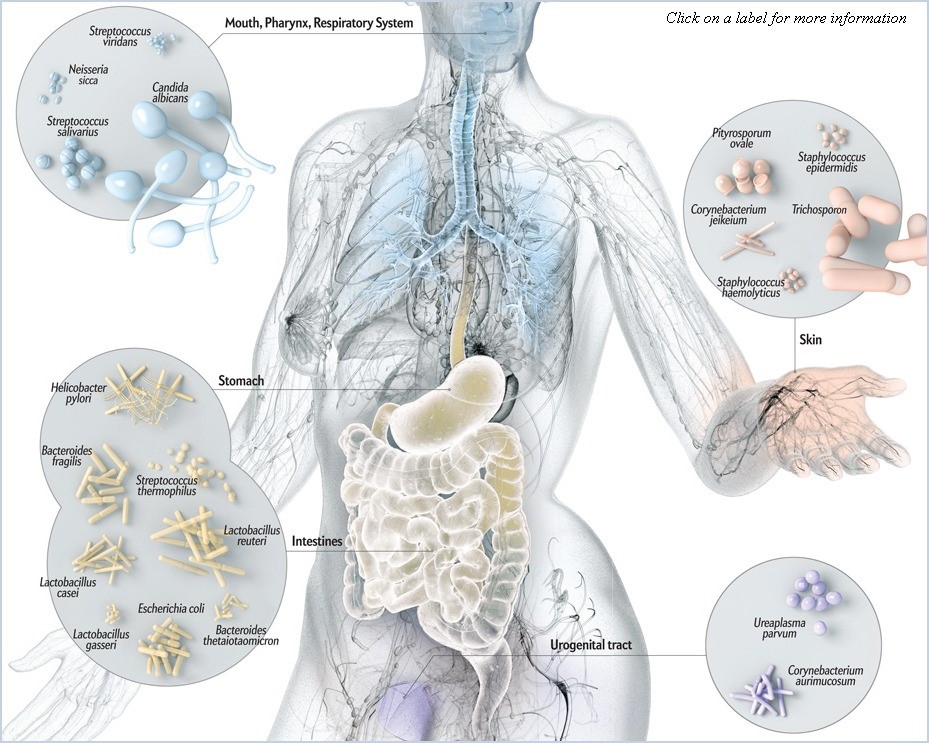

The organisms that colonize the human body are certainly not plants; they are bacteria, yeasts, fungi, viruses, archaea and other microorganisms. Their habitation within and their introduction to your body has a profound influence on your future health, initiated long before you are born.

Understanding the difference between Microbiota and Microbiome

The terms ‘microbiota’ and ‘microbiome’ are a more accurate reflection of the microorganisms residing in and on the human body, yet the terms are often misused:

• Microbiota: refers to all microbial species associated with humans

• Microbiome: refers to the catalog of these microbes + their genes

The microbiota of humans consists of approximately 10-100 trillion microbial cells. Put into perspective, this is approximately ten times the population of the human cells in your body.

Your microbiome comprises as much as 3% of your body mass. Primarily, microbes reside in the gut; however, no surface of the human body is free of them.

Where else do you find your Microbiota?

Your skin, respiratory tract (including the lungs), and urogenital tracts are teeming with microbial life.

Many of these organisms are symbionts; they live within other organisms, such as us! In the majority of cases, this symbiotic living arrangement benefits both the microbes and their host.

Some members of the microbiota are pathogenic (disease-causing). Their populations are smaller and unable to cause disease until the surrounding environment changes to favor their growth.

Microbiome research is taking place worldwide, aiming to understand the role of the microbiota in human health. Here is what the current body of research has uncovered.

The human microbiota is highly specialized

Knowledge of the different microbial species present during times of health versus disease, between individuals and between various sites on the same individual is not new; this was established as early as the 17th century.

Modern medical science wants answers to these questions:

- Why do these differences exist?

- What affects the transformations from one state, person or site to another?

Research has established that microbes of the human gut are not acquired merely from the environment in which we live. Evolution has carefully selected a specific community of bacteria that flourish in the stable, warm and nutrient dense environs of the human gut.

Everything you touch and eat introduces microbes to your body, every day. It appears that the most diverse microbial communities are located in the oral cavity and the gut. We can postulate this is due to their role in eating, as no other sites come into contact with literally thousands of microbial samples (foods) in quite the same way as your mouth and digestive tract. The Hologenome Theory of Evolution questions that natural selection is not merely based on an individual organism, but the organism together with its attendant microbial populations.

Figure One: The Human Microbiome. Source: http://imgbuddy.com/human-microbiome.asp

What influences the colonization process?

Approximately one-third of the human gut microbiota is the same in all individuals. The remaining two-thirds are specific to each individual. It is fascinating to consider that our microbiome is as diverse as fingerprints, our faces, and our genetic profile.

Diversity can be influenced by the following factors:

- Method of infant delivery. Some research suggests that cesarean delivery may impact on early biodiversity of intestinal bacteria. Babies delivered vaginally are exposed to mother’s microbes much sooner, instantly initiating colonization of the infant. Other research suggests there is little difference in microbial colonization between babies delivered vaginally versus C-section by the time they are 3 years old.

- Dietary interventions. Babies who are breastfed are colonized early via microbes from mothers skin. Research also shows that breastfed infants have higher levels of gut microbes in general. The introduction of solids also has a significant impact on a breastfed baby’s microbial population, as it begins to look more like the profile of a formula fed baby.

- Pharmaceutical interventions: Antibiotic treatment is the most well-known drug therapy for causing dysbiosis, but the evidence is mounting for other drugs too, such as oral antacid medications and anti-diabetic medicines and oral contraceptives.

- Longer term dietary changes. Science continues to show the inseparable link between an individual’s microbiota, digestion, and metabolism. Some studies suggest that dietary modifications can influence microbial populations within a week or even a day of the eating pattern shifting.

- Environmental interventions: individuals with highly antiseptic environs have less diversity in their microbiome.

Take away points

- A balanced gut microbiota assists with proper digestive function. As it exists at the interface between food nutrients and the intestinal lining, it assists in breaking down foods left partially digested by the stomach and small intestine.

- Your microbiota is like an army, preventing resurgence and attack from pathogenic microorganisms.

A balanced microbiota helps fulfill the body’s production of some B vitamins and vitamin K. - The interface provided by your microbiota is an immune barrier. Dysbiosis (unbalanced gut microbial populations) is linked with all significant immune disorders, such as allergy, atopy, recurrent infections, autoimmune disorders, some cancers, cardiovascular disease and many chronic digestive disorders.

- Prebiotics act as nourishment for gut microbiota. They induce both the growth and metabolism of beneficial members of the microbiome. Prebiotics are non-digestible fibers such as inulin, pectin, starch, beta-glucans and various oligosaccharides (complex sugars).

- Probiotics are live microorganisms that are supplied via food, beverages (notably fermented or soured types) and supplementation.

Simply taking an over the counter probiotic may not be enough to fully restore the healthy function of our microbiota, or replenish populations of healthy gut microbes and treat dysbiosis. Your diet possibly needs to change. You may require specific species of microbes, or even individual strains of microbes to regain health. Knowing how long to take probiotics, prebiotics and what nutritional changes to make should be undertaken with a complementary or integrative health professional to achieve the results you need and to stop problems recurring for you in the future.

Written by Annalies Corse BMedSc, BHSc.

References

1. Biasucci, G. et al. (2008). Cesarean delivery may affect the early biodiversity of intestinal bacteria. The Journal of Nutrition. 138 (9) 1796S-1800S.

2. Guaraldi, F, and Salvatori, G. (2012). Effect of breast and formula feeding on gut microbiota shaping in newborns. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 94.

3. Gut Microbiota World Watch. Public Information Service from the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. Last updated: January 2016. Available at: http://www.gutmicrobiotawatch.org/en/gut-microbiota-info/

4. Jakobsson, H., et al. (2014). Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonization and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by cesarean section. Gut. Apr; 63 (4): 559-66.

5. Salvucci, E. (2014). “Microbiome, holobiont and the net of life”. Critical Reviews in Microbiology: 1–10.

6. Turnbaugh P., (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 444:1027–1031.

7. Ursell, L. et al. (2012). Defining the Human Microbiome. Nutrition Reviews. Aug; 70 (Suppl 1): S38–S44.